In: How to be Alone

Jonathan Franzen

Picador

New York

2003

32 pages

According to the Art:

Franzen looks back to describe his father’s experience with progressive dementia, while worrying that his memories may be unreliable—yielding a literary meta-analysis of failing memory through inherent memory failings.

Synopsis:

In one of the essays in this collection, Jonathan Franzen tells the story of his father’s slow and inexorable decline from Alzheimer’s disease. His story is a familiar one, and one that millions of people can now tell: at first the initial odd behaviors and memory failures attributed to various causes other than dementia, then the diagnosis and medical interventions to stem the inevitable, and finally the inevitable. While Franzen also describes the toll his father’s dementia exacts on the immediate family, as well as some truths it uncovers about his parents’ marriage, he does not put a significant emphasis on family effects.

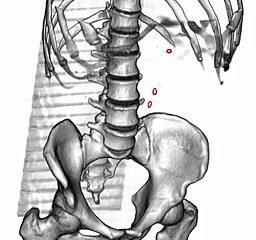

Interwoven in Franzen’s recounting of his father’s plight are a few digressions on Alzheimer’s disease. In one he wonders, as many others have, about whether Alzheimer’s disease is more a medicalization of certain behaviors than the result of brain pathology, or otherwise just “ordinary mental illness being trendily misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s.” (p. 19) In others, he briefly summarizes the well-known theory involving plaques and neurofibril tangles as a cause of Alzheimer’s, and thoughts on how memories form and work in the brain. In yet one other digression, Franzen reminds us that Alzheimer’s disease as originally described in 1906 was a rare type of dementia characterized by early onset in middle age and rapid progression. He further notes that it was not until the latter part of the twentieth century when Alzheimer’s disease was tagged as the fifth-leading cause of death and the “disease of the century,” and only through the efforts—a movement—of a coalition comprising clinical scientists, politicians, and patient advocates.

Analysis:

If Franzen’s tale is not new, and if none of the digressions bring us new insights on Alzheimer’s disease, then why should we read his essay? The reason is the literary approach he takes to isolate and render the most profound consequence of his father’s experience, the loss of memory. He consciously brings his own memory into how he records, interprets, and describes his father’s experience. Franzen gives us a sense of his father’s experience through the varying reliability of his own memory.

He introduces memory as his trope in the first line of the essay: “Here’s a memory.” (p. 7) He then subsequently brings memory in to indicate how well it is serving any particular part of the story:

And yet I have no memory of… (p. 15)

But even then, as far as I can remember… (p. 19)

I remember my suspicion and annoyance… (p.19)

My memories of the week that followed are mainly a blur… (p. 26)

I remember remembering… (p. 27)

…what I chose to remember and retell. (p. 31)

I don’t like to remember how impatient I was for my father’s breathing to stop… (p. 37)

And then in the last instance, “There would be no new memories of him.” (p. 38)

Franzen admits to worrying about the unreliability of memory to get history right. He tells how he became dependent on his mother’s letters because they were “truer and more complete than my self-absorbed and biased memories.” (p. 33) “I couldn’t tell a clear story of my father without those letters.” The letters were for him a “crutch of memory.” (p. 32) Alas, Franzen doesn’t tell us why he put so much trust into his mother’s letters, which are products of her memory as well.

Franzen’s essay prods us to think not only about the memory experience of people with Alzheimer’s disease, but also about the memory experience of those who are observing and reporting on it. Memory is not a binary function where people have it or don’t, a point made clear in this essay.

Also:

Thanks to Alexis Teagarden, PhD, for bringing this essay to my attention.

A version of this review is posted here at the NYU Literature, Arts and Medicine.